Episode 208: St. Joseph’s Orphanage

St. Joseph’s Orphanage in Burlington, Vermont first opened their doors in 1854 and remained open all the way through 1974. It was the temporary home to over 13,000 children from the time of its opening to when the doors closed permanently. From the outside it seemed like this was an establishment that did a lot of good for the children who ended up in their care, but after they closed in 1974, accusations and allegations of horrific abuse began and only grew as more and more survivors came forward.

St. Joseph's Orphanage was founded by Bishop Louis DeGoesbriand, who was also Vermont's first Catholic bishop. The orphanage was first built in downtown Burlington and was run by a group of nuns called the Sisters of Providence, who were actually based just a few hours away in Montreal. The Sisters of Providence often dispatched nuns to serve around Canada, the northern areas of the United States as well as in Chile, so running an orphanage was not outside of the realm of what they were used to. When asking the Sisters for help, Bishop DeGoesbriand wrote “Teach the young and care for the sick and the orphans.” The Diocese then placed chaplains at the orphanage to manage the chapel and church services and run all of the Catholic-specific happenings. Despite Vermont being a small state, there was a huge need for orphanages and care homes for children whose parents either did not want them, could not care for them or had passed away. Most of the children who found themselves at the orphanage were from broken homes or families suffering from poverty, neglect, abuse, or were children of single, unwed mothers.

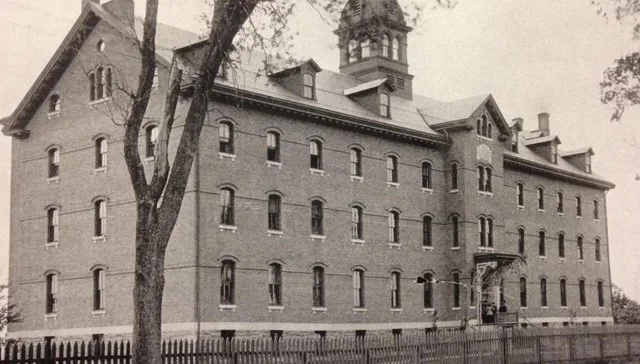

The amount of children needing a facility like an orphanage only skyrocketed throughout the Civil War, and during the middle of the war the population at the orphanage reached over 120 children. By the late 1870’s, the orphanage was bursting at the seams with children and Bishop DeGoesbriand began building a much larger building outside of the downtown area and towards the outside of Burlington. Establishments like St. Joseph’s orphanage were initially viewed as something positive and much needed, but any kind of regulatory boards or safeguards did not come until later in the 1900’s, decades after orphanages and similar facilities had been established and up and running.

By 1912, more than 200 children were living at the orphanage, and this did not include children that were part of the day program where they would be dropped off for care during the day and then picked up and taken home at night. To keep track of all of these kids and keep everything organized, children were assigned a number. They were called by and referred to as their number rather than by their names. Girls and boys were kept away from one another and kept separate at all times, and no exceptions were made for brothers and sisters as siblings of opposite genders weren’t allowed to see each other unless at school, during chapel service or if there was a special event. Children were kept on a strict routine, starting their days at sunrise and attending prayer services and school. As the culture shifted and there were more resources for families and new legislation, by the 1960’s and 1970’s, the deinstitutionalization movement began focusing on taking people and children out of orphanages, asylums, mental health facilities and state hospitals and caring for them in the community. After the facility closed for good, it seemed as though the orphanage was just another piece of history and the past. That is, until the allegations began coming out.

In June of 1993, just under 20 years after St. Joseph’s closed, a lawsuit was filed by a man named Joey Barquin. Joey was living in Florida at the time, but he had been a resident of St. Joseph’s Orphanage. In the lawsuit, he said he was brutally beaten and molested by a nun as a child in the early 1950’s. Joey had recently gotten married, and he was taken aback when his wife was shocked and had a visceral reaction to seeing his genitals. This was because when Joey was a little boy, a nun had dragged him out of his room, into a private room, and made him pull down his pants. She proceeded to fondle him and then slice at his genitals with a sharp knife, causing horrific permanent scarring and a significant amount of bleeding in the moment after the attack. Joey said he had witnessed an extensive amount of abuse from the nuns towards other children as well. He had watched other children be brutally beaten, he had seen a little girl be thrown down a flight of stairs that left her bleeding out of her nose and ears, and a boy who was shaken so violently and for so long that he went into a state of shock.

Joey’s wife had encouraged him to go to therapy, but the most therapeutic thing would be for Joey to get an apology. After he spoke to two priests at the diocese and was essentially brushed off, he wanted to sue. The state's Roman Catholic Diocese did what they do best and tried to not only fight the allegations but hide them and sweep them under the rug entirely. The church ended up settling out of court three years later for an amount described in “the low six figures.” The exact amount has not been disclosed. Joey’s bravery in coming forward, not only with what he endured but his bravery in calling on the entities responsible to face what they did, was absolutely monumental. When his story came out, it inspired multiple other people to come forward about their own stories of abuse at St. Joseph’s orphanage. Soon, the numbers of other people who had faced unimaginable abuse as children soared.

Survivors recounted emotional, physical, mental, sexual abuse from nuns, staff and religious higher ups. 28 former residents of the orphanage ended up bravely filing lawsuits, whether in state or federal court, against Vermont Catholic Charities, the Sisters of Providence and the diocese as a whole. In the 1980’s, lawyer Philip White set up systems that made it easier to report abuse. After he filed for Joey Barquin’s case, 40 additional victims contacted him. Philip White ended up winning in court in November of 1994, not just for Joey but the other 40 abuse survivors as well. The statute of limitations at the time was only six years from when victims understood the injury they had suffered, which really put a damper on things with the victims seeking justice after coming forward decades later.

Joey Barquin ended up settling out of court in 1996, but soon went to attorney Robert Widman to continue pursuing his case. Robert Widman also filed a case with another victim and resident of the orphanage that same year in 1996. Her name was Sally Dale, and her coming forward was also monumental. The three defendants were the Diocese of Burlington, Vermont Catholic Charities, and the Sisters of Providence, and the church filed a motion to dismiss Sally’s case. The diocese also paid $5,000 to the 60 St. Joseph’s residents in exchange for their silence. Plaintiffs said as many as 160 individuals pursued the bishop’s offer for the $5,000.

Philip White looked at all of his clients who ended up taking the offer and then sent a letter on their behalf to Bill O’Brien, the church’s attorney. Excerpts from the letters state:

“Dear Bill. K remembers that Sister Madeline and Sister Claire … slapped her head and face, pulled her hair, struck her face with the backs of their hands, so that their rings split her lips, and tripped her and knocked her down.”

“Dear Bill … To this day, C will not enter a closet if it has a hanging light.”

“Dear Bill … If L was caught not paying attention, the nuns would take a needle and regularly prick his fingertips.”

“Dear Bill … The nuns would also force G and other children to hold their arms up at their sides, with their palms up in the air, balancing a book on the palms. If G dropped his arms before the requisite time was up, he would be beaten and forced to repeat the punishment all over again.”

Three years later in August of 1996, Joey Barquin and the other victims ended up settling “for a significant amount of money” and strict instructions to keep that amount and the agreement a secret. The church continued to settle, with some survivors getting $120,000 and $150,000. By 2006, more survivors kept coming forward and the church began looking at individual settlement claims of $1 million. As the price tag began to climb, the bishop then put 130 parishes into trusts that could be used for “pious, charitable or educational purposes” in the hope of generating some good press as well as a distraction to the abuse allegations that were only increasing. This was also a strategic move in the sense of hoping to financially shield the church from any further abuse liability.

This sparked a much larger investigation into multiple priests who were suspected of molesting children. Author of the book “Ghosts of the Orphanage” Christine Kenneally stated “In all, I was stunned to discover that at least twelve and as many as seventeen male clergy members [and five laypeople] who had lived or worked at St. Joseph’s or Don Bosco—the connected home for boys on the same grounds as St. Joseph’s—had been accused of, or were treated for, the sexual assault of minors.” It was found that from 1935 until the orphanage closed in 1974, at least six of St. Joseph’s eight resident chaplains, who were the priests who oversaw the orphanage, had been accused of sexual abuse. Those six: Fathers Foster, Bresnehan, Devoy, Colleret, Savary, and LaRouche, oversaw St. Joseph’s during most of its final forty years of existence. This meant that during that time, there were only two years where the priest in charge of the orphanage did not turn out to be a publicly accused abuser.

Unfortunately many of the survivors had their childhoods and essential formative years shaped by years of horrific abuse, and this led to some developing substance abuse issues, PTSD, and struggles with mental health. Something that is overwhelming with the survivors that came forward and advocated not just for themselves but for those who were not able to speak up is the amount of bravery they showed with challenging an entity as huge as the Catholic church. In August of 2018, their efforts and the horrors from within the orphanage gained international attention after Australian journalist Christine Kenneally wrote a huge investigative article for BuzzFeed titled “We Saw Nuns Kill Children: The Ghosts of St. Joseph's Catholic Orphanage." Within this article, which has first-hand accounts from interviews with survivors and members of involved legal teams, exposed an especially heinous crime: a murder.

A woman named Sally Dale told of her firsthand encounter of seeing a child die after being pushed out of a window on the fourth floor of the orphanage by a nun. She described seeing the child hit the ground and then hit the ground a second time after bouncing on impact, and that she looked up and saw a nun’s habit and her arms extended out in a pushing motion. The nun then accused Sally of having a wild imagination and then threatened her with abuse, stating “We are going to have to do something about you, child.” She also recalled vomiting and then the nuns using her face to wipe up her own vomit. One of the nuns had yelled “You will not be this stubborn! You will sit and you will eat it.” Sally reported that the memories of the full extent of the abuse and horrors in the orphanage were buried in her mind until she went to a group where other survivors were talking about what happened and the memories began coming back. This caused her a lot of pain and emotional distress.

Sally’s report of witnessing a murder caught the attention of the world, and also made its way back to Vermont Attorney General T.J. Donovan. Although most of the sexual assault cases were unfortunately quite limited due to statute of limitations, murder is not limited by this and the Attorney General’s office announced that they would do an investigation. Attorney General T.J. Donovan also announced that he would be convening a St. Joseph's Orphanage Task Force. The Task Force was to be made up of people from the Attorney General’s office as well as State Police, local police in Burlington, and other officials who were all taking this claim very seriously. The Task Force also announced their recommendation of doing a massive and separate restorative process for orphanage survivors so that they could come together to talk about what they had endured with others who had also been impacted.

After a thorough investigation, the Task Force determined that over the 120 years the Orphanage operated, roughly 435 children died from various causes. Most of the deaths were a result of illness, and almost all of these deaths were before 1933. However, the Task Force did not receive adequate information about where the children who died had been buried. In the meantime, the Diocese commissioned its own study about priest sexual abuse at the orphanage and in general, and their 2018 Independent Report on Priest Sex Abuse Cases said that five priests assigned to posts at the orphanage were credibly accused of sexual abuse of children.

The Task Force completed their investigation in 2020, and their report said that they were unable to find evidence of the murder of the child being pushed out of the window. They did state “It is clear that trauma occurred. It was the insidious type that bore no physical scar or bruise, the type that indelibly shapes the survivors' lives to this day. It was this constant emotional abuse and diminishment that forced survivors to live in constant fear and caused lifelong trauma… The State of Vermont, its laws, and its institutions did not protect all of the children of St. Joseph's Orphanage. That failure to protect was a failure of the laws, a failure of law enforcement, and a failure of the society that made those laws and oversaw their enforcement. We today are willing to acknowledge that we failed to protect these children. Our hope is, through the restorative process, some form of justice and closure can be achieved for the survivors."

The Voices of St. Joseph’s Orphanage founded a Restorative Inquiry, which went into great detail about their plans to bring restoration to those impacted by the events at the orphanage. The project was largely ran by survivors themselves, who said that the group’s purpose was to:

1. Memorialize the iterative development of the SJORI process, from inception to conclusion.

2. Offer cumulative learning and practice reflections to other communities and interested-parties considering a restorative response to institutional harms.

3. Invite and share personal reflections from the core participants, facilitators, and stakeholders to the process.

A quote from the restorative inquiry states “Imagine what it must have been like to be a scared young child, removed from your only family, and sent into an institutional setting to live with other children from similarly difficult backgrounds. Shut off from contact with the outside world, you were put in the custody of intolerant strangers with little or no training in child care. Some of them were actually sadistic. Life was unthinkable for thousands of children placed in that orphanage. We suffered physical, mental and, in some cases, sexual abuse. We were threatened and punishment was harsh, swift, and extreme. Oh the horrors! We were beaten with rods, locked in dark closets and trunks, and forced to eat our own vomited food. Some were sexually molested, this by the same people professing to be agents of God: Catholic nuns, priests, Edmundites, and other workers at the facility. Some children did not survive their time there; they simply ‘disappeared.’ The orphanage was closed in the late 1970’s without anyone ever bringing to light what really went on inside its walls. Then, in the mid-1990’s, when some of our truths began to emerge, some of us brought lawsuits against the diocese. Sadly, those cases were thrown out due to technicalities or legal grounds; some former orphans were even paid hush money (a pittance, really) to keep them quiet! The effect of these failed suits in the 1990’s was profound; having the hope that justice would be served only to have it dashed felt like being victimized all over again. We were suppressed and intimidated again by those in power and standing in the community. Now, thanks to an extensive report produced in 2018 for Buzzfeed, written by Christine Kenneally, the State Attorney General’s Office has conducted an investigation into our claims about what happened at St. Joseph’s Orphanage. The truth deserves to be aired; cover up tactics should be widely exposed.”

Image sources:

pcavt.org - “St Joseph’s Orphanage: Many Reasons to Learn and Acquire Prevention Skills”